My research

Jason Koski/University Photography

Jason Koski/University Photography

The trio that started the gravitational lensing project: Will Throwe, Andy Bohn, Francois Hebert

Quick links to my research

- Gravitational lensing - A really exciting project is trying to answer the question “What do merging black holes really look like?”

- toroidal event horizons - My thesis is primarily focused on studying the topological properties of event horizons during a merger

Getting started

When I was in grade school and first learned that mysterious objects called black holes existed, a few questions that instantly popped into my head were:

- What does a black hole really look like?

- What would happen if you fell into a black hole?

- What happens when one black hole tries to eat another black hole?

At the time, I didn’t know how to find serious answers to these questions, and they unfortunately lay dormant in the back of my mind for another decade or so.

Fast forward to my first summer of graduate school at Cornell University in 2011, when the budding students were supposed to try and find a research group to start a fruitful research career with many research papers (or something like that). My friend Francois told me he wanted to study black holes and neutron stars with Saul Teukolsky. In an instant all of my questions about black holes came flooding back to the forefront of my mind, and I was fortunate enough to start to pursue questions about black holes with Saul straight away!

What my group studies

I work in the Simulating eXtreme Spacetimes (SXS) collaboration studying merging black holes and neutron stars. Here’s a little bit of backstory:

Einstein’s theory of General Relativity makes a whole host of predictions that can be experimentally verified. One important example is that light is bent in a particular way by gravity, so light rays passing by the sun are slightly bent around the sun.

Another example is GPS, which could not properly operate without relativity. GPS operates by satellites in orbit sending messages that say what time the message was sent as well as which satellite sent the message. A GPS device receives these messages, computes how far away each satellite was, then triangulates its location. For a GPS device to be accurate to about 15 meters, the GPS satellites must be accurate to about 50 nanoseconds (50 nanoseconds = 15 meters / speed of light). An interesting consequence of general relativity is that time ticks more slowly when in a stronger field of gravity than otherwise. GPS satellites orbit 12,600 miles above the surface of the Earth and experience a four times weaker field of gravity than on the surface, so the satellite clock is about 45 microseconds faster per day than a clock on Earth. Without General Relativity (and Special Relativity for similar timing reasons), GPS would have significant issues to deal with.

As technology and ingenuity advances, we have been able to test more and more of the theory with increasing accuracy, and the theory has passed with flying colors. General relativity also predicts the existence of something called gravitational waves.

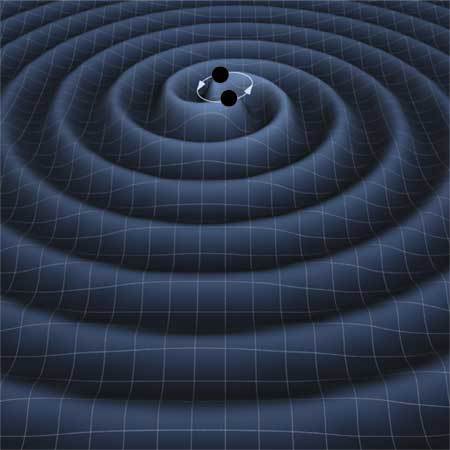

Einstein’s theory of general relativity describes gravity as an intrinsic property of space and time. Sources of gravity cause space and time to become curved, and all objects in the universe simply try to move in straight lines in this curved spacetime. The moon orbiting the Earth is following a straight line in the curved spacetime near the Earth, which causes it to orbit. Gravitational waves are ripples in the curvature of spacetime.

Directly detecting gravitational radiation would be another large step in the process of testing the validity of general relativity. However, being unable to detect gravitational radiation, or detecting radiation that we didn’t expect would start an incredible journey in discovering entirely new physics!

One of the primary goals of my research group is to aid in the detection of gravitational radiation. I’ll explain this more in a page about detecting gravitational waves.

What I study

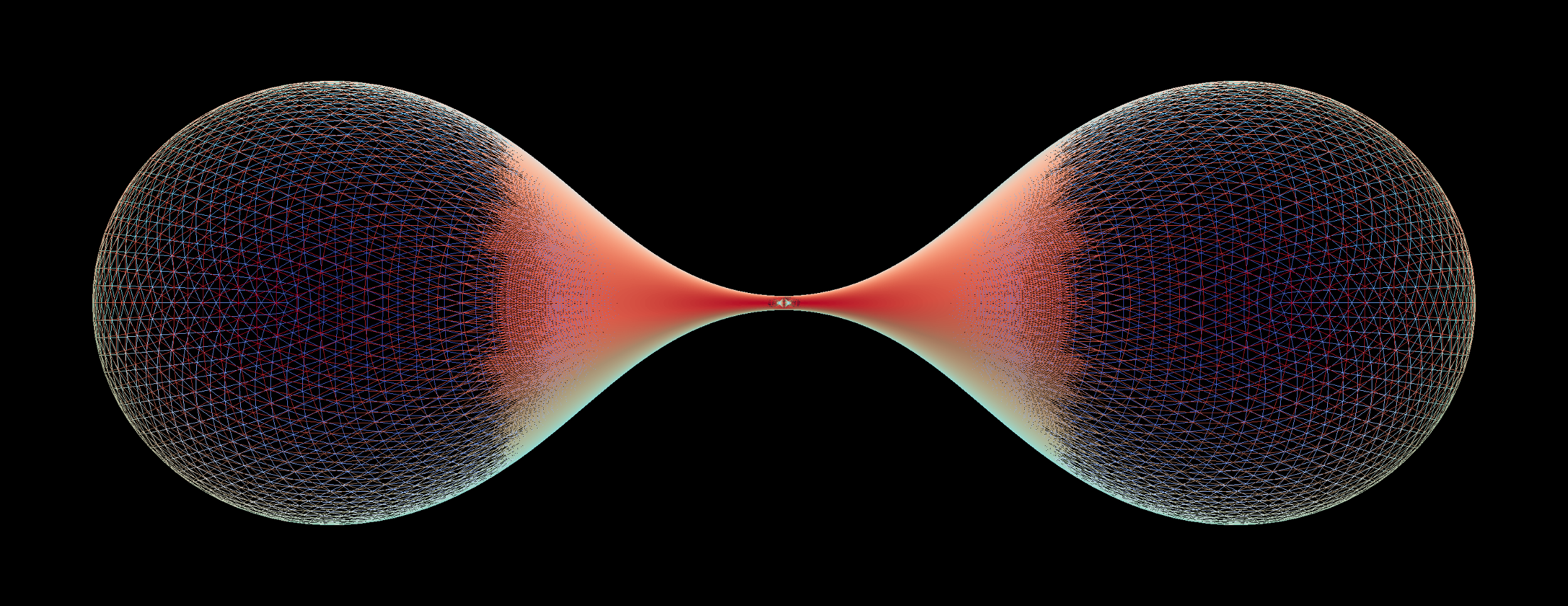

The primary focus of my thesis work is studying how the event horizons of two black holes join together to form a single black hole. Here’s a page that explains more about my studies on event horizons. The banner art at the top of this page shows the event horizons of two black holes running directly into each other.

I also spent some time studying what black holes, and even merging black holes really look like! Here’s a page that explains gravitational lensing. The banner art on the home page and the about me page show off some output of our gravitational lensing work.